Hadrian’s wall is an enigmatic frontier of the Roman Empire situated at the northern end of England and stretching from Wallsend in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west. While it is often viewed as the frontier to ‘separate the Barbarians from the Romans’, it was more than that.

From a customs barrier to a military frontier to a political statement, the wall transformed and changed throughout the Roman Empire’s reign in Britain. Even after the end of the Roman Empire, the wall had its own meanings that changed the way it was viewed, with the Anglo-Saxons and the Early English and Scottish Kingdoms drawing meaning from it. Today we view it as a heritage monument and a bit of British history.

In this blog, we’ll provide a summary of the ways the wall changed over the course of its history and how we interpret it today as we look to the future.

Before the wall

Around 2500BC the majority of white British people descended from the Beaker people. Jumping forward to 1000BC, a secondary migration of ‘Celts’ came in from near the Swiss and French Alps. They settled in today’s southeast of England. We also have descriptions from Julius Caesar’s Gallic Wars, and other contemporary historians, of migrations from Gaul into the British Isles with offshoots of the Belgae living on the south coast of England. We do not know how many other migrations there were or where they came from. Caesar himself divided the people of Britain into different groups saying those in the north were similar to the Germanic peoples and Scandinavians, those in the west were more similar to the Portuguese and Spanish, and those in the south more similar to the Belgians. It’s important to note that Caesar massively simplified a great deal of anthropological content to make it easy to understand while justifying his actions, thereby increasing his fame back in Rome.

From 43 AD to 90 AD we saw the expansion of Roman forces, firstly in the south-east of England under Claudius, then moving into the west of what is now England and Wales with Nero’s commanders. From 60 AD onwards there was a campaign in northern Britain due to the revolts of the Brigantes against the Queen Cartimandua, led by her ex-husband. These revolts caused Roman governors to establish the Stanegate forts, which we know best as the Roman forts of Corbridge, Vindolanda, Magna and Carlisle.

Under Agricola, the Romans pushed right up into North East Scotland and were building a legion fortress at Inchtuhil in the Highlands, which would have held two whole legions. In Roman Romania, Dacia revolted and the Romans suffered heavy casualties across Eastern Europe. This resulted in troops being drawn from the northern British border across to Dacia to fight. Inchtuhil was dismantled and it is likely that the Roman frontier was pulled back to the area of the Scottish borders and North Northumberland with the two most northerly forts at Newstead and Dalswinton. Lines of forts were along roads eventually leading back to the Stanegate – a rough line drawn between Corbridge and Carlisle.

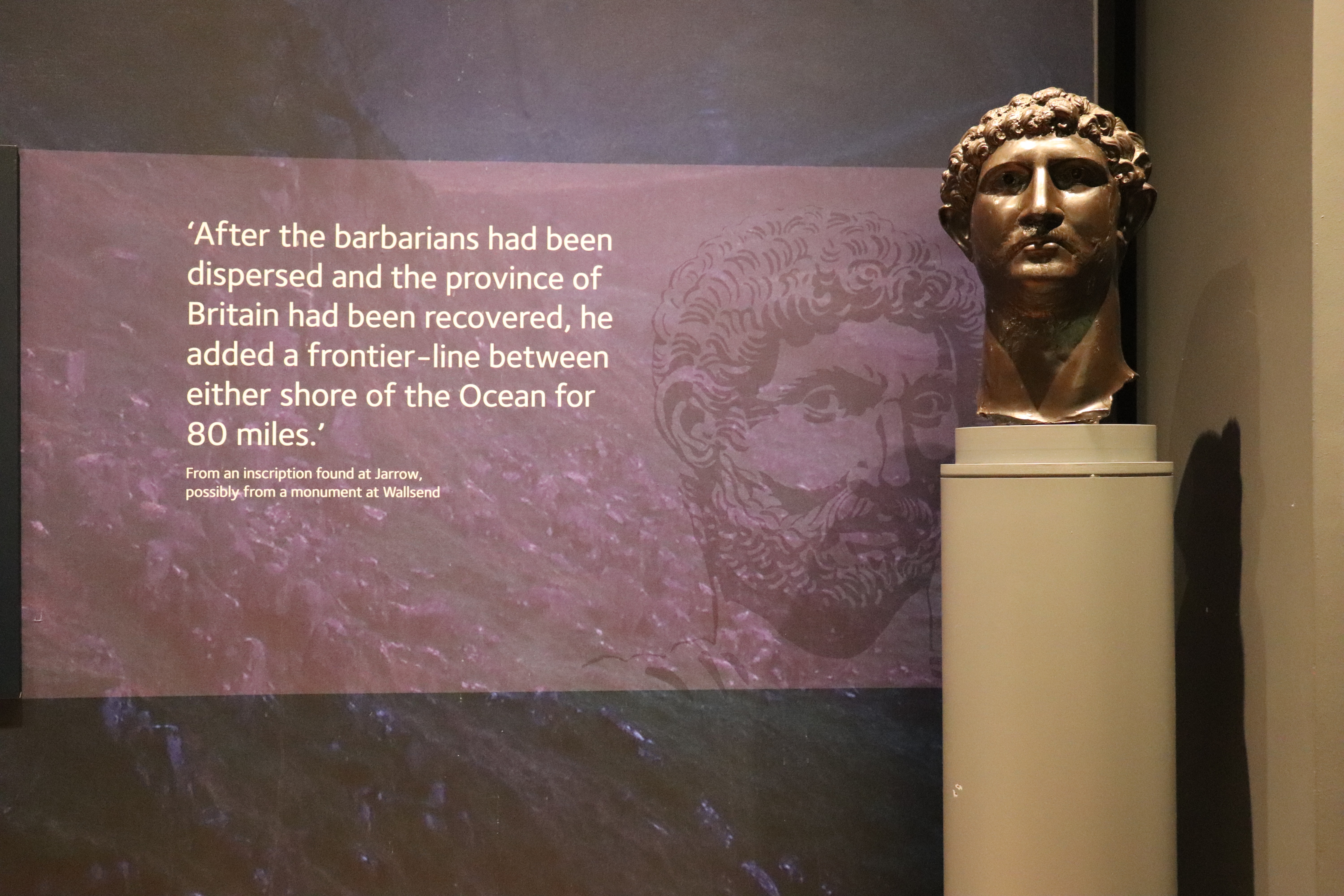

The construction of Hadrian’s Wall

It was following the death of Emperor Trajan and the consolidation of Emperor Hadrian that Hadrian’s wall was started, in around 120AD. Once built, more conflict flared up and more troops in the sixth legion were brough in to complete the construction of the wall. War forts were added to reinforce the defensive properties of the towers and mall castles originally built.

Eventually, the wall was completed and began its function to defend and control Northern Britain. The wall itself only retained its functionality until the death of Hadrian whereupon his successor Antonius Pius needed a victory of his own and so pushed the frontier up to his own named ‘Antonine Wall’. Many of the troops stationed on Hadrian’s wall moved up to the Antonine Wall and it appears many of the gateways and doors on Hadrian’s Wall were left open to allow easy movement North and South. Parts of the Vallum were filled in and, for around 25 years, the Antonine Wall was a new frontier of the Roman Empire. However, in the three years leading up to Antonius Pius’s death the frontier was abandoned and Hadrian’s wall was re-established.

Hadrian’s Wall as a commercial and military frontier

In the third century AD, under the reign of Septimus Severus the Romans pushed again into what is now Scotland. He oversaw repairs to the wall and erected several dedications to himself along the wall. Arbeia Roman fort was re-constructed as a supply depot for this campaign and his troops caused devastation in today’s Scotland, leading to a period of peace lasting almost the whole century.

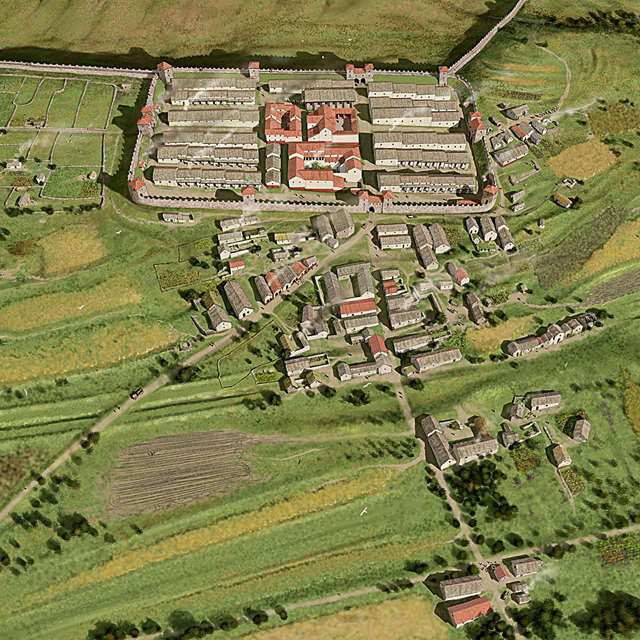

Towns like Carlisle and Corbridge grew during this time as Vici- civilian settlements – were introduced behind the forts on Hadrian’s Wall. It is thought that the vicus at Benwell may have stretched as far down as the Tyne with industrial and civilian quarters. Excavations in recent years have found buildings that could be up to three stories in height as well as evidence of possible coal mining in and around the vicus of the Roman fort of Condercum. There is even evidence to suggest that construction occurred north of the wall in locations such as Wallsend, Benwell and Housesteads. Though this may appear foolish it shows the security that the civilian population and military authorities felt following Septimus Severus’s campaign.

In the third century Housesteads Roman Fort appears to have had its own factories for creating weapons and armour and expanded its own food and accommodation capacity. A huge store building was also constructed during this period that was used until the end of the occupation within the fort.

During the fourth century, the Roman army was at its strongest and construction continued at Housesteads. The massive storage building was upgraded to house the bathhouse and other changes continued to happen right up until the fort was abandoned.

There is also evidence at Segedunum for chalet style buildings. The chalets are thought to be easier to construct than the larger century barrack blocks that had existed in the second and early to mid-third centuries, requiring fewer resources. The shorter wooden beams combined with a high level of carpentry would have been more than enough to provide accommodation for the soldiers.

Evidence of churches at Housesteads and Vindolanda indicated the new religion of the empire extended to the furthest reaches of the northern frontier.

After the Romans

After the end of the Roman period there is good evidence for continued inhabitation of the sites. Roundhouse buildings were built over the top of the ruins. At Vindolanda a monastery was built into the site of the previous Roman fort. This continued to be in use until the eighth century where the growth of Hexham and Hexham Abbey likely resulted in the Christian community moving to Hexham.